29. juli 2015

Robert Draper, National Geographic, slriver bl.a.

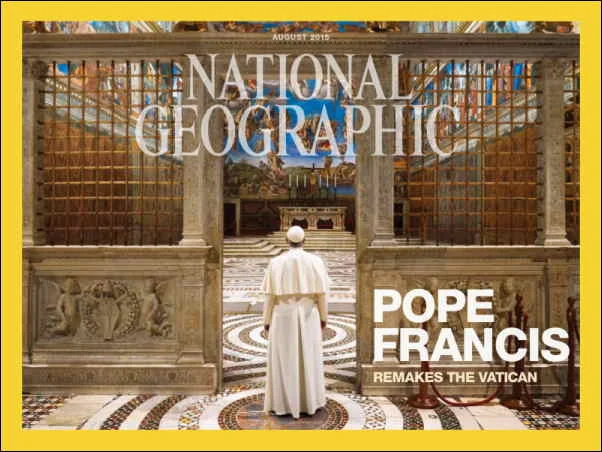

Will the Pope Change the Vatican?

Or Will the Vatican Change the Pope?

As Francis makes his first U.S. visit, his emphasis on serving the poor over enforcing doctrine has inspired joy and anxiety in Roman Catholics.

When about 7,000 awed strangers first encounter him on the public stage, he is not yet the pope—but like a chrysalis stirring, something astounding is already present in the man. Inside Stadium Luna Park, in downtown Buenos Aires, Argentina, Roman Catholics and evangelical Christians have gathered for an ecumenical event. From the stage, a pastor calls out for the city’s archbishop to come up and say a few words. The audience reacts with surprise, because the man striding to the front had been sitting in the back all this time, for hours, like no one of any importance. Though a cardinal, he is not wearing the traditional pectoral cross around his neck, just a black clerical shirt and a blazer, looking like the simple priest he was decades ago. He is gaunt and elderly with a somber countenance, and at this moment nine years ago it is hard to imagine such an unassuming, funereal Argentine being known one day, in every corner of the world, as a figure of radiance and charisma.

He speaks—quietly at first, though with steady nerves—in his native tongue, Spanish. He has no notes. The archbishop makes no mention of the days when he regarded the evangelical movement in the dismissive way many Latin American Catholic priests do, as an escuela de samba—an unserious happening akin to rehearsals at a samba school. Instead the most powerful Argentine in the Catholic Church, which asserts that it is the only true Christian church, says that no such distinctions matter to God. “How nice,” he says, “that brothers are united, that brothers pray together. How nice to see that nobody negotiates their history on the path of faith—that we are diverse but that we want to be, and are already beginning to be, a reconciled diversity.”

Hands outstretched, his face suddenly alive, and his voice quavering with passion, he calls out to God: “Father, we are divided. Unite us!”

Those who know the archbishop are astonished, since his implacable expression has earned him nicknames like “Mona Lisa” and “Carucha” (for his bulldog-like jowls). But what will also be remembered about that day occurs immediately after he stops talking. He drops slowly to his knees, onstage—a plea for the attendees to pray for him. After a startled pause, they do so, led by an evangelical minister. The image of the archbishop kneeling among men of lesser status, a posture of supplication at once meek and awesome, will make the front pages in Argentina.

Among the publications that carry the photograph is Cabildo, a journal considered the voice of the nation’s ultraconservative Catholics. Accompanying the story is a headline that features a jarring noun: apóstata. The cardinal as a traitor to his faith.

This is Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the future Pope Francis.

----

An Unmanageable Pope

When Federico Wals, who had spent several years as Bergoglio’s press aide, traveled from Buenos Aires to Rome last year to see the pope, he first paid a visit to Father Federico Lombardi, the longtime Vatican communications official whose job essentially mirrors Wals’s old one, albeit on a much larger scale. “So, Father,” the Argentine asked, “how do you feel about my former boss?” Managing a smile, Lombardi replied, “Confused.”

Lombardi had served as the spokesman for Benedict, formerly known as Joseph Ratzinger, a man of Germanic precision. After meeting with a world leader, the former pope would emerge and rattle off an incisive summation, Lombardi tells me, with palpable wistfulness: “It was incredible. Benedict was so clear. He would say, ‘We have spoken about these things, I agree with these points, I would argue against these other points, the objective of our next meeting will be this’—two minutes and I’m totally clear about what the contents were. With Francis—‘This is a wise man; he has had these interesting experiences.’”

Chuckling somewhat helplessly, Lombardi adds, “Diplomacy for Francis is not so much about strategy but instead, ‘I have met this person, we now have a personal relation, let us now do good for the people and for the church.’”

The pope’s spokesman elaborates on the Vatican’s new ethos while sitting in a small conference room in the Vatican Radio building, a stone’s throw from the Tiber River. Lombardi wears rumpled priest attire that matches his expression of weary bemusement. Just yesterday, he says, the pope hosted a gathering in Casa Santa Marta of 40 Jewish leaders—and the Vatican press office learned about it only after the fact. “No one knows all of what he’s doing,” Lombardi says. “His personal secretary doesn’t even know. I have to call around: One person knows one part of his schedule, someone else knows another part.”

The Vatican’s communications chief shrugs and observes, “This is the life.”

Life was altogether different under Benedict, a cerebral scholar who continued to write theological books during his eight years as pope, and under John Paul II, a theatrically trained performer and accomplished linguist whose papacy lasted almost 27 years. Both men were reliable keepers of papal orthodoxy. The spectacle of this new pope, with his plastic watch and bulky orthopedic shoes, taking his breakfast in the Vatican cafeteria, has required some getting used to. So has his sense of humor, which is distinctly informal. After being visited in Casa Santa Marta by an old friend, Archbishop Claudio Maria Celli, Francis insisted on accompanying his guest to the elevator.

“Why is this?” Celli asked. “So that you can be sure that I’m gone?”

Without missing a beat, the pope replied, “And so that I can be sure you don’t take anything with you.”-

Hele artiklen er <her>