Vi er i Polen, 1945. Mathilde, en ung fransk Røde Kors-læge, er på en mission for at hjælpe overlevende fra krigen. Da en nonne søger hendes hjælp, bliver hun bragt til et kloster, hvor flere søstre er blevet gravide efter overgreb af de sovjetiske soldater. Nonnerne kan ikke forene deres tro med deres graviditet og Mathilde bliver deres eneste håb.

I filmen medvirker Lou de Laage, som var en af Shooting Stars på Berlin Film Festival og Agata Kulesza fra “Ida”.

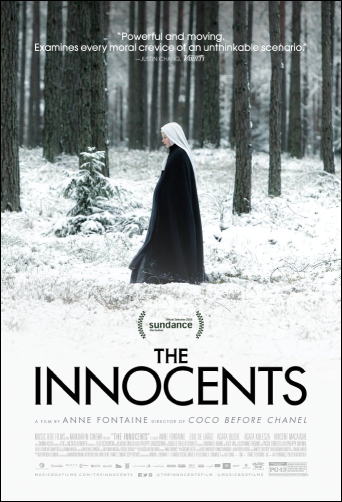

De Uskyldige er instrueret af Anne Fontaine som tidligere har lavet "Coco før Chanel".

Premiere dato: 5. jan. 2017

Billetter - Kino.dk <her> / eBillet <her>

Forpremiere d. 4 jan i Gloria Biograf & Café: <her>

De uskyldige bliver præsenteret af Damian Nawarecki, der er født i Polen, men har boet i Danmark siden 1969, hvor han arbejder som oversætter i fransk. Ud over sin viden om efterkrigstidens Polen og det franske sprog er han katolik og har derfor en meget personlig indgang til filmens religiøse og kulturelle temaer.

Efter filmen byder Det Franske Kulturinstitut på et godt glas vin.

Original titel Les innocentes (USA: Agnus Dei)

Land/år: Frankrig, Polen/2016

Skuespillere: Lou de Laâge, Agata Buzek, Agata Kulesza

Instruktør: Anne Fontaine

Manuskript: Pascal Bonitzer

Les Innocentes - en bemærkelsesværdig film, der bygger på en virkelig historie

december 1945 i et snedækket efterkrigstids Polen, stadig dybt mærket af krigens traumer. Det er advent og i et benediktinerkloster ude på landet synger nonnerne i liturgien om det barn, der skal fødes i julen og bringe frelse og fred: 'trøst mit folk, snart skal din frelse komme...'

6 af dem venter et andet barn, de er gravide, efter at russiske soldater- befrielseshæren - 9 måneder tidligere invaderede klostret og voldtog nonnerne gennem, tre døgns mareridt. To døde, andre blev gravide, en blev smittet med syfilis. Alt må holdes skjult, kommer det ud, hvad der er sket og nu foregår, vil klostret blive opløst og nonnerne sendt på gaden i skam og vanære. Så de føder uden hjælp, en er allerede død i barselsseng, og børnene sørger abbedissen for at få bortadopteret hurtigst muligt, eller det er i hvert fald hvad søstrene tror. Midt i en kompliceret fødsel, der trækker i langdrag, søger en novice hjælp uden om abbedissen i den nærliggende landsby, hvor en fransk rødekorsmission arbejder. En kvindelig fransk læge- kommunist, ateist - involveres- først noget modvilligt, og søstrene er ligeledes afvisende i et frontalt kultursammenstød, men efterhånden bliver lægen optaget af den situation, hun finder i klosteret og af de mennesker, der lever der, og som søger at bevare tro og kald i denne situation, der udfordrer alt, de hidtil har kendt.

Bevægende film- værd at se!

Interview med instruktøren Anne Fontaine

I USA er filmen lanceret under titlen "Agnus Dei".

Agnus Dei is inspired from a little-known true event that occurred in Poland in 1945.

The story of these nuns is incredible. According to the notes taken by Madeleine Pauliac, the Red Cross doctor who inspired the film, 25 of them were raped in their convent - as much as 40 times in a row for some of them - 20 were killed and 5 had to face pregnancy. This historical fact doesn’t reflect well on the Soviet soldiers, but it’s the truth; a truth that authorities refuses to divulge, even if several historians are aware of the events. These soldiers didn’t feel they were committing a reprehensible act: they were authorized to do so by their superiors as a reward for their efforts. This type of brutality is unfortunately still widely practiced today. Women continue to be subjected to this inhumanity in warring countries around the world.

What was your initial reaction when the producers, the Altmayer brothers, came to you with this project?

I was immediately taken with the story. Without really understanding why, moreover, I knew that I had a very personal connection with it. Motherhood and self-questioning with regard to faith were themes I wanted to explore. I wanted to get as close as possible to what would have been happening within these women, to depict the indescribable. Spirituality had to be at the heart of the film.

Are you familiar with matters of religion?

I come from a Catholic family - two of my aunts were nuns - so I have a few connections in regards to the subject. But I can only work on a theme if I know it perfectly well and I wanted to experience what life in a convent was like from the inside. I felt it was important to learn about a nun’s daily routine, understand the rhythm of her days. I went on two retreats in Benedictine communities - the same order as the one in the film. I was only there as an observer during the first retreat, but I truly experienced the life of a novice in the second.

Tell us more about it.

Beyond life in a community, which impressed me a great deal - this way of being together, praying and singing seven times a day - it’s also as if you were in a world where time is suspended. You have the feeling of floating in a type of euphoria and yet you are bound by a very strong discipline. I saw how human relationships were established: the tension and shifting psychology of each person. It’s not a frozen, one dimensional world. But what touched me the most, and what I attempted to convey in the film, is how fragile faith is. We often believe that faith cements those who are driven by it. That’s an error: as Maria confides to Mathilde in the film, it is, much to the contrary, “twenty-four hours of doubt for one minute of hope.” This notion sums up my impressions after speaking with the sisters, and also after attending a conference about questioning one’s faith given by Jean-Pierre Longeat, the former Abbot of Saint-Martin de Ligugé Abbey. What he said was extremely moving and has a profound echo within today’s secular world.

Were the members of these religious communities aware of your project?

Fortunately, the people I met immediately had a favorable opinion of the project even if there were complicated truths revealed about the Church. We share, along with the sisters, the paradoxical situation that they are forced into as a result of being attacked: how to face motherhood when one’s entire life has been committed to God? How to keep one’s faith when confronted with such terrible facts? What to do faced with these newborns? What are the possibilities available?

Had these priests and nuns seen your previous films?

They had seen some of them, The Girl from Monaco and Coco Before Chanel in particular. One monk confided that one of his favorites was Adore [Perfect Mothers]. I have to admit that I was rather surprised.

You also bring up the deviations that religion can lead to… an example would be the Mother Abbess’ attitude, which, under the pretext of not letting anyone know what was occurring at the convent, prohibits the sisters from receiving proper medical care.

The film raises questions that haunt our societies, and shows what fundamentalism can lead to.

Yet you do not judge the Mother Abbess.

It was extremely difficult to construct and balance out this protagonist. We may deem appalling the acts she commits. But I quickly realized that, without toning down her actions, we had to try and understand her interior motives. I wanted her to explain herself with this ambiguous statement that she pronounces before the sisters: “I’ve damned myself to save you.” When she begs for God’s help, and when we see her ill in bed, without her veil, we can tell that she has been drawn into an abyss. This type of character role can easily become caricatured. Without Agata Kulesza, who is exceptional, I don’t know if the Mother Abbess would have had this interiority or brought this dimension, reminiscent of Greek tragedy.

The film has a unique rhythm: it’s quite meditative despite its fast pace.

I wanted to convey the singular, meditative passage of time in a convent while maintaining the dramatic tension: It was a delicate balance to find both while writing the screenplay and during the film shoot. I also replicated what I saw during my

retreats. I thought it was important to know that the sisters grant themselves peaceful moments when everyone can pursue their own interests: reading, music, sewing, conversation…

--

FROM REALITY TO FICTION: THE STORY OF MADELEINE PAULIAC

When she was 27 years old, Madeleine Pauliac, a doctor on staff at a Paris hospital, joined the resistance movement, providing supplies and lending support to allied parachutists. She then participated in the liberation of Paris and in the Vosges and Alsace military campaigns.

At the beginning of 1945, as a lieutenant-doctor in the French Interior Forces, she left for Moscow under the authority of General Catroux, the French Ambassador in Moscow, to direct the French repatriation mission.

The situation in Poland was dramatic. Warsaw, a martyred city after 2 months of insurrection against the German occupant (between August and October 1944) had been razed to the ground causing the death of 20,000 combatants and 180,000 civilians. During this time, the Russian Army, present in Poland since January 1944 under Stalin’s orders, remained armed and waiting on the other bank of the Vistula River. After a backward surge from the German Army and the discovery of

all the acts of violence committed by the Germans,the Red Army and its provisional administration followed to rule over the liberated territories.

It’s within this context that Madeleine Pauliac was named in April 1945 Chief Doctor of the French Hospital in Warsaw, which was in ruins. She was in charge of repatriation within the French Red Cross. She conducted this mission throughout Poland and parts of the Soviet Union. She accomplished over 200 missions with the Blue Squadron Unit of women volunteer ambulance drivers for the Red

Cross in order to search for, treat and repatriate French soldiers who had remained in Poland. It’s in these circumstances that she discovered the horror in the maternity wards where the Russians had raped women who had just given birth as well as women in labor; individual rapes were legion and there were collective rapes perpetrated in convents. She gave medical care to these women.

She helped them to heal their conscience and save their convent. Madeleine Pauliac died accidentally while on a mission near Warsaw in February 1946.

Agnus Dei recounts this episode of her fight as a woman to save other women.

- Philippe Maynial, Madeleine Pauliac’s nephew

"Anne Fontaine's finest film in years observes the crises of faith that emerge in a war-ravaged Polish convent"

- Variety - Sundance review

"Anne Fontaine delves into a traumatised convent in Poland in late 1945, in this gripping and accomplished film boasting some excellent actors"

- Cineuropa

"A must-see film that quietly suggests a surprising answer to the problem of evil."

- Christianity Today

Wikipedia: De uskyldige (The Innocents)